Hank Aaron

Hank Aaron's 715th Home Run

April 8, 1974

Atlanta Stadium

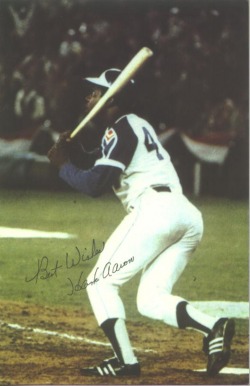

Before an Opening Night crowd of 53,775, Hank Aaron blasted his 715th home run, surpassing Babe Ruth and becoming the home run king of baseball.

Aaron's fourth-inning homer came on a 1-0 pitch from Los Angeles pitcher Al Downing.

Aaron's fourth-inning homer came on a 1-0 pitch from Los Angeles pitcher Al Downing.

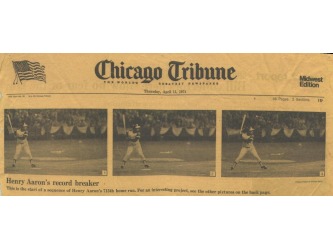

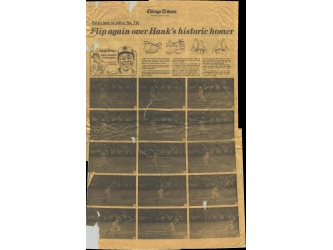

Chicago Tribune 'Flip'

Thursday April 11, 1974, three days after Hank's record-breaking slam, the Chicago Tribune published an 'extra' where 18 sequenced photos of the historic swing were featured. The fan could clip the 18 slides, stack them in order, then page - or flip - through them quickly to see a replay.

The 18 photos were scanned and made into an electronic flip book in YouTube. To see the flip book, click on the YouTube video below.

Farewell party

The Milwaukee Brewers honored the all-time home run king with 'A Salute to Hank Aaron Night' on September 17, 1976.

Below is a scan of the original newspaper article from The Milwaukee Journal; the converted text document is below that.

Below is a scan of the original newspaper article from The Milwaukee Journal; the converted text document is below that.

Milwaukee Journal Sports

Saturday, September 18, 1976

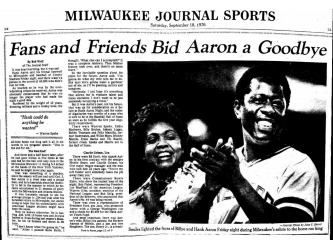

Fans and Friends Bid Aaron a Goodbye

By Bob Wolf

of The Journal Staff

It was heartwarming, but it was sad.

Hank Aaron said his formal farewell to Milwaukee and baseball at County Stadium Friday night and there wasn’t a person in the crowd of 40,383 who didn’t feel for him.

As touched as he was by the overwhelming tribute he received, Aaron was obviously embarrassed that he was no longer the player who had made the night a good idea.

Burdened by the weight of 42 years, dimming reflexes and a creaky knee, the all-time home run king said it all in six words in his pregame speech: “This is the end for me.”

The Real End?

And three and a half hours later after he had gone hitless in five times at bat and had hit the ball well only once in the Milwaukee Brewers’ 11 inning 5-3 defeat at the hands of the New York Yankees, he said he might never play again.

That was something of a shocker, since the season will not end until Oct. 3. But Aaron is a tired man and a proud man, and he is heartsick about his inability to hit in the manner to which he became accustomed in 21 seasons of glory with the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves. It was traumatic enough to see his average plunge to .234 last year after his heralded return to Milwaukee, but Aaron clung to hope that his unfamiliarity with American League pitchers might have been the cause.

Now he knows otherwise. He is batting .230, with 10 home runs and 34 runs batted in. Even during last season’s disaster, he hit 12 homers and drove in 60 runs.

“I don’t know what I’m gonna do,” he said. “After I passed Babe Ruth, I thought ‘What else can I accomplish?’ It was a complete letdown. Then Mother Nature took over, and there’s no more there.”

To the inevitable question about his plans for the future, Aaron said. “I’m gonna do what my wife tells me to do. She says she’s gonna make a gardener out of me, so I’ll be planting carrots and tomatoes.”

“Seriously, I just hope its something that allows me to evaluate talent and make decisions. I don’t want to be just somebody occupying a room.”

But it was Aaron’s past, not his future, that was up for consideration on A Salute to Hank Aaron Night, and the roster of dignitaries was worthy of a man who’s sure to be in the Baseball Hall of Fame as soon as he fulfills the five year eligibility requirement.

There were Warren Spahn, Eddie Mathews, Billy Bruton, Johnny Logan, Bobby Thomson and Felix Mantilla, former teammates, and Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Ernie Banks and Vic Raschi, former rivals. Spahn and Mantle are in the Hall of Fame.

Charlie Grimm, Too

There were Ed Scott, who signed Aaron to his first contract with the semipro Mobile Bears, and Charlie Grimm, his first major league manager and the man who told him 22 years ago, “You’re my left fielder until somebody takes the job away from you.”

There were Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who drew the loudest boos of the night; Bob Fishel, representing President Lee MacPhail of the American League; Warren Giles, president emeritus of the National League, and Bud Selig, president of the Brewers, who announced that Aaron’s No. 44 was being retired.

There was even a representative of President Ford, son Jack, who presented Aaron with a George Washington cup and a check for $5,400 for the Hank Aaron Youth Fund.

And most important, there was Aaron’s wife, Billye; his parents, the Herbert Aarons of Mobile, and a son and two daughters. The son, Henry Jr., is a freshman tight end on the University of Arkansas football team.

Three Ovations

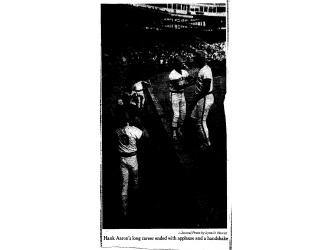

Aaron received no fewer than three standing ovations — one of two minutes when he took the rostrum for the ceremonies, one of three minutes when he got up to speak, and one of a mere 30 seconds when he went to bat for the first time.

After the longest of the three had finally died down, he told the crowd, “This is one of the saddest times of my life, to reach the age when I have to bow out of baseball. I’ve been extremely lucky to play this long, and I want to thank you wonderful fans. I’ve never played before such great fans in my life.”

Old opponents and friends alike heaped praise on the man who has broken too many records to mention.

Mantle, for example, said, “He was the most underrated player of our era for a superstar. You kept hearing about Mays and me, but if he’d been playing in New York, he would have been with us.”

Mays commented, “People used to compare Hank with me, but we were two different players, one a center fielder and one a right fielder. He was the best right fielder in baseball.”

The Four Credits

Raschi, who served up the first of Aaron’s 755 home runs, said, “He had the four credits. He could run, throw, hit and field. When a guy has all that, what more can you say?”

Bruton remarked about Aaron’s quickness as a learner, saying, “He didn’t look too good in the outfield at first. He was awkward getting to a ball, But he became a good outfielder in a hurry, and there was never any question about his hitting.”

And it remained for Spahn, who by a remarkable coincidence had been similarly honored exactly 13 years before, to tell just what a great athlete Aaron had been.

Said Spahn: “Hank could do anything he wanted to do. If he had wanted to be a pitcher, he could have been a 20 game winner. He wanted to be a complete ballplayer, so he stole 40 bases. He wanted to outdo Mathews, so he became a home run hitter. Who ever thought he would he a home run hitter?”

Ability and Desire

“He wanted to be the best, and he had both the ability and the desire to do it. He was so great, I thought he’d hit .400 some day.”

Along with the emotion and nostalgia, there was one bit of levity.

Aaron’s Brewer teammates presented him with a battered car, fresh from Crazy Jim’s Demolition Derby, and an estimated 13 of them crowded into it with pitcher-humorist Jim Colborn at the throttle.

Printed on the windshield was “44cents,” and on the side, “755 home runs: Who cares? How many strikeouts?”

Asked what make of car it was, Colborn said, “It’s a 1971 Torino Canardly. You roll it down a hill and you canardly get it up.”

After pulling the heap to a stop and waiting for half the Brewer team to pile out, Colborn yelled at Aaron, “Where do you want me to park it?’

Aaron was laughing too hard to answer, and the comic relief was one of the best things that happened to him all evening.

Saturday, September 18, 1976

Fans and Friends Bid Aaron a Goodbye

By Bob Wolf

of The Journal Staff

It was heartwarming, but it was sad.

Hank Aaron said his formal farewell to Milwaukee and baseball at County Stadium Friday night and there wasn’t a person in the crowd of 40,383 who didn’t feel for him.

As touched as he was by the overwhelming tribute he received, Aaron was obviously embarrassed that he was no longer the player who had made the night a good idea.

Burdened by the weight of 42 years, dimming reflexes and a creaky knee, the all-time home run king said it all in six words in his pregame speech: “This is the end for me.”

The Real End?

And three and a half hours later after he had gone hitless in five times at bat and had hit the ball well only once in the Milwaukee Brewers’ 11 inning 5-3 defeat at the hands of the New York Yankees, he said he might never play again.

That was something of a shocker, since the season will not end until Oct. 3. But Aaron is a tired man and a proud man, and he is heartsick about his inability to hit in the manner to which he became accustomed in 21 seasons of glory with the Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves. It was traumatic enough to see his average plunge to .234 last year after his heralded return to Milwaukee, but Aaron clung to hope that his unfamiliarity with American League pitchers might have been the cause.

Now he knows otherwise. He is batting .230, with 10 home runs and 34 runs batted in. Even during last season’s disaster, he hit 12 homers and drove in 60 runs.

“I don’t know what I’m gonna do,” he said. “After I passed Babe Ruth, I thought ‘What else can I accomplish?’ It was a complete letdown. Then Mother Nature took over, and there’s no more there.”

To the inevitable question about his plans for the future, Aaron said. “I’m gonna do what my wife tells me to do. She says she’s gonna make a gardener out of me, so I’ll be planting carrots and tomatoes.”

“Seriously, I just hope its something that allows me to evaluate talent and make decisions. I don’t want to be just somebody occupying a room.”

But it was Aaron’s past, not his future, that was up for consideration on A Salute to Hank Aaron Night, and the roster of dignitaries was worthy of a man who’s sure to be in the Baseball Hall of Fame as soon as he fulfills the five year eligibility requirement.

There were Warren Spahn, Eddie Mathews, Billy Bruton, Johnny Logan, Bobby Thomson and Felix Mantilla, former teammates, and Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Ernie Banks and Vic Raschi, former rivals. Spahn and Mantle are in the Hall of Fame.

Charlie Grimm, Too

There were Ed Scott, who signed Aaron to his first contract with the semipro Mobile Bears, and Charlie Grimm, his first major league manager and the man who told him 22 years ago, “You’re my left fielder until somebody takes the job away from you.”

There were Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who drew the loudest boos of the night; Bob Fishel, representing President Lee MacPhail of the American League; Warren Giles, president emeritus of the National League, and Bud Selig, president of the Brewers, who announced that Aaron’s No. 44 was being retired.

There was even a representative of President Ford, son Jack, who presented Aaron with a George Washington cup and a check for $5,400 for the Hank Aaron Youth Fund.

And most important, there was Aaron’s wife, Billye; his parents, the Herbert Aarons of Mobile, and a son and two daughters. The son, Henry Jr., is a freshman tight end on the University of Arkansas football team.

Three Ovations

Aaron received no fewer than three standing ovations — one of two minutes when he took the rostrum for the ceremonies, one of three minutes when he got up to speak, and one of a mere 30 seconds when he went to bat for the first time.

After the longest of the three had finally died down, he told the crowd, “This is one of the saddest times of my life, to reach the age when I have to bow out of baseball. I’ve been extremely lucky to play this long, and I want to thank you wonderful fans. I’ve never played before such great fans in my life.”

Old opponents and friends alike heaped praise on the man who has broken too many records to mention.

Mantle, for example, said, “He was the most underrated player of our era for a superstar. You kept hearing about Mays and me, but if he’d been playing in New York, he would have been with us.”

Mays commented, “People used to compare Hank with me, but we were two different players, one a center fielder and one a right fielder. He was the best right fielder in baseball.”

The Four Credits

Raschi, who served up the first of Aaron’s 755 home runs, said, “He had the four credits. He could run, throw, hit and field. When a guy has all that, what more can you say?”

Bruton remarked about Aaron’s quickness as a learner, saying, “He didn’t look too good in the outfield at first. He was awkward getting to a ball, But he became a good outfielder in a hurry, and there was never any question about his hitting.”

And it remained for Spahn, who by a remarkable coincidence had been similarly honored exactly 13 years before, to tell just what a great athlete Aaron had been.

Said Spahn: “Hank could do anything he wanted to do. If he had wanted to be a pitcher, he could have been a 20 game winner. He wanted to be a complete ballplayer, so he stole 40 bases. He wanted to outdo Mathews, so he became a home run hitter. Who ever thought he would he a home run hitter?”

Ability and Desire

“He wanted to be the best, and he had both the ability and the desire to do it. He was so great, I thought he’d hit .400 some day.”

Along with the emotion and nostalgia, there was one bit of levity.

Aaron’s Brewer teammates presented him with a battered car, fresh from Crazy Jim’s Demolition Derby, and an estimated 13 of them crowded into it with pitcher-humorist Jim Colborn at the throttle.

Printed on the windshield was “44cents,” and on the side, “755 home runs: Who cares? How many strikeouts?”

Asked what make of car it was, Colborn said, “It’s a 1971 Torino Canardly. You roll it down a hill and you canardly get it up.”

After pulling the heap to a stop and waiting for half the Brewer team to pile out, Colborn yelled at Aaron, “Where do you want me to park it?’

Aaron was laughing too hard to answer, and the comic relief was one of the best things that happened to him all evening.